I interviewed both authors mentioned below when their debut poetry collections were first published earlier this year. I wrote this review around the same time, but despite my luck with getting my own individual pieces published I have had less luck placing reviews, so I'm posting this double act here for your appreciation.

Ancient

Lights (Phoenicia Publishing, 2012), Dick Jones,

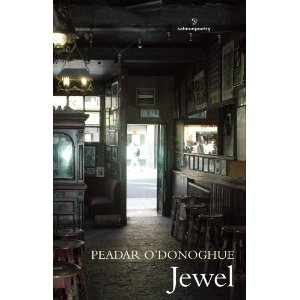

and Peadar O’ Donoghue’s Jewel (Salmon

Poetry, 2012)

Dick Jones’ debut is titled Ancient Lights but it is the sense of

sound that transfixes us in the first poem of the collection ‘Stille Nacht’.

‘On the night/ that I was born/ the bells rang out’ chimes the first stanza,

comparing worship to carolling ‘In Auschwitz-Birkenau’ where ‘the story goes,/

the death’s-head guards/ sang, “Stille

nacht,/ heilige nacht”’, and it

is sound that transports us through the title poem and beyond.

‘Ancient Lights’

begins self-referentially, knowingly: ‘Banded light, I should remember first’

before exploding into synaesthesia. Each stanza culminates with song so that ‘The

conductor haunted/ the stairs in black. We crooned’ fills us with the notion of

song being history’s ghost; music therefore, Jones urges us to listen, is

time’s time-traveller, a way in to the historical events through what was the

primary escapism of those times. We listeners travel chronologically as linear

voyeurs ‘on a dim swell of voices’ to ‘a house’ as if of creation, but here

Jones reveals his conceit, ‘that’s there already,’ and is ‘free of pain/ and

ghosts,’ ending inarguably with ‘fruit/ that falls and germinates/ at random

when/ and where it will’, the last line tapering to a single apple drop; the

sound of a full stop.

‘And time and

place/ conspired:’ in ‘Mr Moore’s Wall-Clock’ evoking for this reader the

school rhymes of Yorkshire and of Henry Clay Work’s ‘My Grandfather’s Clock’

and Charles Kingsley’s ‘The Old, Old Song’ (though one must wonder, given the

poet’s musical background, if it wasn’t Donovan’s ‘When All the World is Young’

playing through his mind when he wrote it) with such lines as ‘And the world

was one green hill, the sky a net’, and ‘Time/ was a circle dance, two hands in

rhyme’. The loved face in Jones’ poetry is recognition, of memory, of walls

blown down, and of new beginnings built from the ruins. Each stanza pushes

forward the narrative like clock workings ‘into shadow, from my midday to Mr

Moore’s midnight.’

So seamlessly

Jones transports us with his watchmaker’s eye from the intricate brass gears to

a ‘First Eclipse’, it is easy to run full pelt through this collection with no

more impediment than a child’s desire to empty out the toy box, only his

language calls us to pause and marvel. The overarching themes of Ancient Lights are not new but they are

brought to the reader with fresh observations and a deft touch leaving one in

no doubt Dick Jones is a new talent, one only wonders why it took so long to

bring him to print.

Born in war – a

beginning from ruins – it is fitting Jones

concludes on the moon. ‘I am elected watchman. It’s my lot’ Jones starts

then turns the words with a thread of irony easy to miss but difficult not to

savour: ‘[…] while man takes giant steps below’. Jones’ collection crescendos ‘like

a choir triumphant’ with its song lingering long after the event has ended.

‘The Old, Old

Song’ sounds again in the epigraph of Peadar O’ Donoghue’s debut collection. ‘I

was never a diamond,’ he explicates, ‘not even a rough one, I can’t polish

pearls of wisdom,/ but this is my jewel.’ And Jewel, the collection’s title, is much the finest metaphor one

could choose to describe O’ Donoghue’s poems; each one gives the sense of its

having been hoarded away for years, polished carefully before being allowed to

shine. But there’s the irony for the subject matter of these poems is not what

one would wish to show off ordinarily. In the title poem a drunk’s thoughts are

brandished defiantly as a whore’s knickers as he personifies the river Liffey:

‘she calls to me in clamshells of desire.’ In this way the poem builds,

throwing together imagery as at odds as pissing and consumption, seemingly with

all the grace of a chip shop server, to justify the speaker’s ‘relief and

satisfaction in equal measure.’ Far from being bawdy the poem is a tour de force

in bathos in spite of its vaudeville guise.

Though seemingly

pained to acknowledge it, O’ Donoghue has literary authority. In ‘Pictures and

Postcards’ we glimpse: ‘Mountains to mist, Beckett to boxer to blonde’, the

allusion dissolving like a cloud to the concrete of the fighter and further to

the artifice of ‘blonde’. There is reserve here that comes to play as control,

there is skill but it is humble; the poems in Jewel down-play themselves, in doing so they demonstrate un-showy

brilliance. O’ Donoghue applies comic book humour to take cliché after cliché and

crush them Superman-like to reveal the diamond inside. ‘“Stay a while” they

seem to say. “Drink your coffee,/ compile this list for lesser days”’ which is

surely what O’ Donoghue has been doing with this collection.

Jewel speaks of an

Everyman man who has lived a place, caught in its traditions until they have

become him. There’s a symbiosis here lending to a Sean O’ Casey poignancy and

politics. In ‘This is a Controlled Poem’ O’ Donoghue lets slip his buffoonish

masque to cane A S J Tessimond-like ‘the voice of reason’. ‘This poem’ is a

rebellion such as only those who have been silenced know. ‘This poem is […]/ a

neatly pressed shirt for the office on Monday.’ Duty here mirrors religious

observance and ritual but in ‘The Birth of a Nation’ any spiritual intervention

is dismissed. ‘It wasn’t a miracle,/ most things are born out of poverty,’ like

Christ. We are reminded of this in ‘This Christmas We’. ‘Stretch the fabric of

life,’ it urges, boldly, then tears its bravado to scraps, ‘reduce,/ re-use,

recycle’ chanted like a drinking song.

O’ Donoghue has

kept his poems in his shirt pocket it seems for half a lifetime, gems cut clean

from the heart; the words of a shining talent don’t need the allusion to let

you know they sparkle, they simply need to be read.